CAMBODIA-FINE-ARTS © 2021 • AGB | DATENSCHUTZ | IMPRESSUM

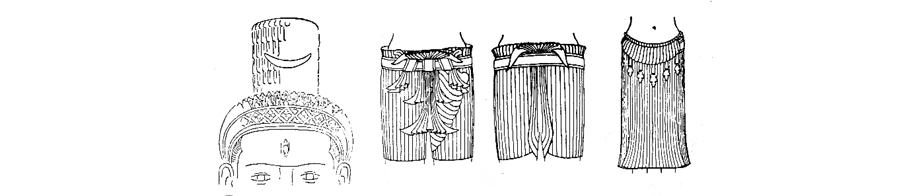

SAMBOR PREI KUK STYLE

Corresponds more exactly to the Tchen La period and the reign of Icanavaman, first third of the seventh century.

Works sculptured in the round of this style are few.

This art follows the preceding one, with hieratic and wide hipped figures, their execution remain dependent on the techniques used in the Phnom Da style. Female statues make their appearance, their modelling is ample and a witness to a perfect knowledge of the anatomy. The morphology of the faces remains very Indian. Its relationship with

Phnom Da Art is more particularly linked to the late sixth, early seventh century. Around 630—640, this art coexisted with the Prei Kmeng style.

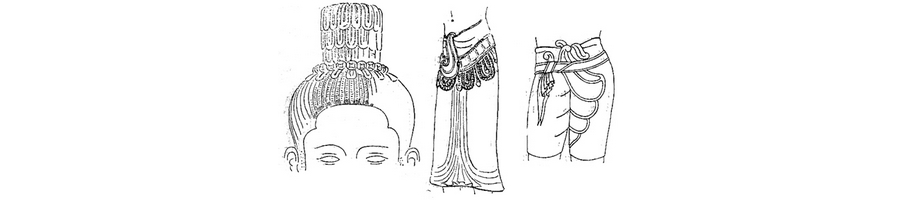

PREI KMENG STYLE

Mid seventh century.

Contemporary art of the reign of Bhavavarman I, who reigned around 635.

The Prei Kmeng style overlaps the end of the Sambor Prei Kuk and co-existed with the following style of Prasat Andet.

Its influence was felt up to the end of the seventh century through the following styles and that of Kompong Preah

The size of the statues diminish. The female divinities are more and more numerous, presenting opulent forms and showing a slighter hip line. New figures appeared, these are the representations of Brahma and Bodhisattva. The supportive arch system remains and is used for statues of four arms or more.

This Is an extremely brilliant art.

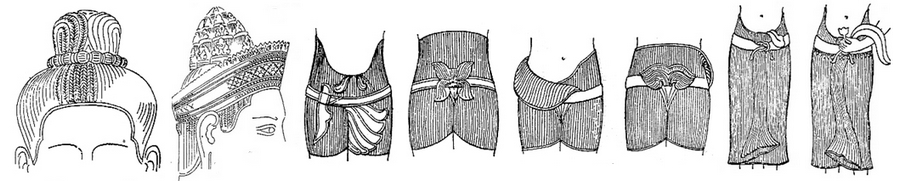

PRASAT ANDET STYLE

Prasat Andet art is situated at the end of the seventh and beginning of the eighth century.

In general it uses the elements of the preceding Prei Kmeng and Sambor Prei Kuk styles

The statues are medium sized and the sculpture is of rather irregular workmanship . The anatomic realism remains a preoccupation which at times the sculptor expresses with much elegance. We note the appearance of a fine moustache which becomes generalized throughout the tenth century.

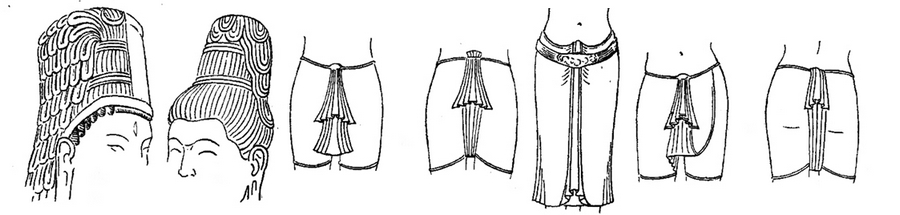

The mitre headdress becomes more present and tends to cover the whole of the scalp

It curves onto the temples, around the ears and covers the nape. At the base of this headdress is a small headband, with a raised row of indents which prefigure the tiara of the Angkorian period.

KOMPONG PREAH STYLE

The style of Komponq Preah developed among the troubles which overwhelmed the country during the the eighth century. For its statues it takes the elements of the two preceding styles.

The silhouette, at times a little heavy for certain statues, announces the aesthetic of the ninth century The form of the hips hardens but the face remains pleasant, often a little cold; coldness increases as we advance in the ninth century.

In general the production is irregular and often mediocre. In comparison to the Prassat Andet style this is one of decline.

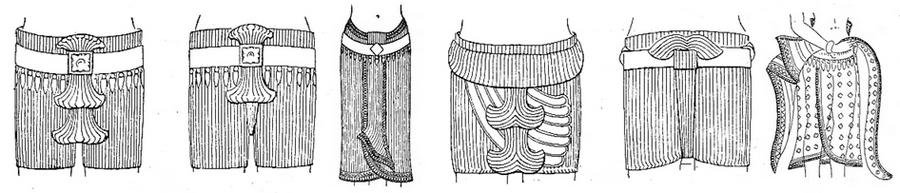

PHNOM KULEN STYLE

This corresponds to the first half of the ninth century and the reign of Jayavarman ll.

This period marks a turning pornt in the evolution of the statues and prepares the transformation towards classic Angkorian Art.

The silhouette of the figures loses in elegance, but gains in vigour: being necessary to express the force and power of the god. The hips are clumsy and not very pronounced. We are far from the refinement of the Hari-Hara of Prasat Andet.

The face, large and calm, a little rigid, shows a continuous and assertive eyebrow line. The moustache which appeared with the Prasat Andet style is better defined. The first tiaras worked by goldsmiths appear along with the chignon headdress. The supportive arch disappears definitively. No female statue of this period has been found - ls this purely circumstantial or does it correspond to a ritual modification?

Kulen Art marked by profound innovations was able to preserve the character of force and the beauty of the masterpiece of the sixth and seventh centuries.

PREAH-KO STYLE

Last quarter of the ninth century.

The Preah Ko style corresponds to the reign of Indravarman (877-889). It uses and accentuates the characteristics of the preceding style.

The tendancy of the Kulen Art towards plumpness becomes outright corpulence. The line of the hips is more and more discreet.

The general silhouette is heavier. The faces become large and unexpressive. The moustache asserts itself and is completed with a beard. The tiara and the chignon headdress become general and announce Angkorian Art.

BAKHENG STYLE

The statues of the Bakheng style correspond to the reign of Yacovarman (889 — after 900).

All the characteristics of the precedent art are found in this style, but exaggerated.

The frontality, the hieratism and the conventional model finish in an Art which is cold and unexpressive, of which the only merit is, perhaps, to have provoked the reaction of the styles of Koh Ker and Banteay Srey.

This is a grandiose Art, denied of all sensitivity.

KOH KER STYLE

After the impoverishment of the Bakheng style with conventional statues lacking in

sensitivity, this is an art of reaction (921 - 945).

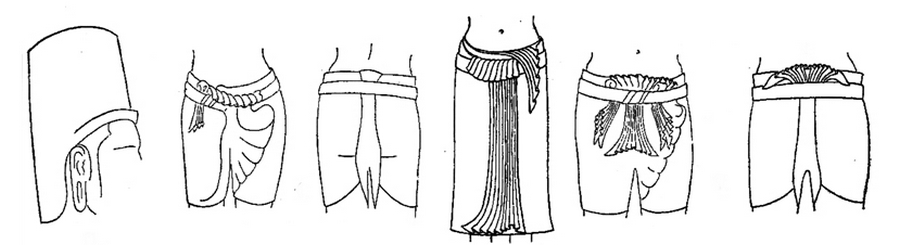

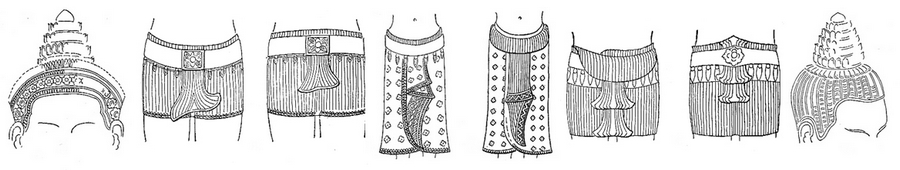

The style uses the preceding tendancy towards monumental and heavy statues, the anatomy remains unchanged, but the faces soften and on some of them, a smile appears. In other respects the adornings take on a new importance, necklaces, double belts, bracelets, and earrings are directly carved in the stone. The tiara, the mukuta and sun curtain are richly decorated.

le appears. in other respects the adornings take on a new impor-

But the most remarkable innovation is, without doubt, the appearance of movement through creations of monumental dimensions. Among the most successful of these is the group of fighting monkeys and the gigantic Garudas at Prasat Thom of Koh Ker chasing the Naga (formula taken from Bakong).

The frontality and hieratism of the preceding styles are no longer an exclusive rule. Movement becomes a privileged means of expression.

This is a new and astonishing Art, even more astonishing due to the difficulty in solving the problems of size and stability posed in its execution.

We are far from the shy sculptures in the round of the beginning, cautiously comforted by powerful supporting arches. We discover audacious works, of monumental dimentions created out of the same block of stone, including pedestal. We are in the presence of a veritable transfer of the Khmer sculptors' know-how.

PRE RUP STYLE

This is an Art of transition, which is mid tenth century and corresponds mainly to the reign of Rajendravarman 944 - 968; The statuary art, like architecture tries to bring up to date the ancient formulae.

Through the rare pieces which have sunrived, we note the use of the hieratism of the Bakheng Art, we find the Koh Ker style of headdress; the Sampot uses the design of those of the beginning of the century. The Size of the statues tend to be smaller. The movement and vitality of the figures innovated by Koh Ker Art appear to be forgotten. This an Art without character which shows a certain lack of vigour. A moment of pause before the following reviving style of Banteay Srei.

BANTEAY SREI STYLE

Later half of the tenth century (967).

The Bantreay Srei style develops at the same time as the Pre Rup style and overlaps that of the Kleang.

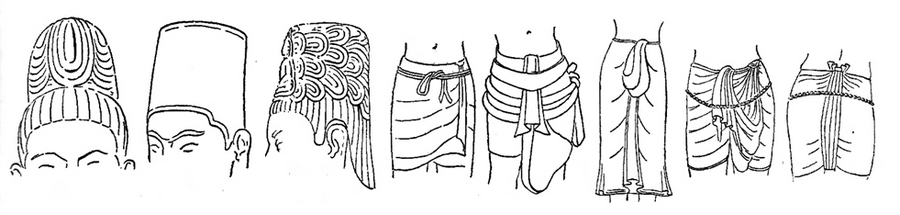

It uses and develops the formulas of the Koh Ker style, the headdress with horizontal tresses, the tiara and the conical mukuta.

The beard and moustache are also kept, but in a more discreet way. The fullness of the forms give the face a softness which accentuates the eyes opened wide, and the fleshy and sensual lips. The hip line is again used, without excluding the hieratism of the preceding style. The waists are slender and the bodies well proportioned. The anato-

my shows a strong sense of observation. The overall silhouette is elegant and a reminder of the Pre Angkorian Art which has perhaps inspired the pleated skirts of some of the statues.

Generally, the statues are small in size, but in scale with the temple, a feeling of elegance and softness is given off by the whole.

KLEANG STYLE

Kleang Art corresponds to the reign of Suryavarman I, in the first half of the eleventh century. Strongly influenced by the Pre Rup and Banteay Srei styles, the statues of the Kleang style, unfortunately, have neither the richness nor the elegance.

Few of these statues have survived. The images are again hieratic, but present a softer form. The faces are pleasant, the hair is in plaits which are lifted onto the top of the scalp in the form of a chignon and the tiara is sporadic. The female skirt tends to be cut below the navel and rises in the back, thus announcing a Baphuon style Art; in the front

is a pleat in the form of a fish’s tail.

In general, the composition is less vigorous than the Banteay Srei period. It is an Art without any marked character but a tendency to perpetuate previous styles.

BAPHUON STYLE

Corresponding to the reign of Udayadityavarman II (1050 - 1066) and largely overlapping the following reign.

Its affiliation with Banteay Srei Art is obvious.

The silhouette is especially elegant. The faces express a great softness, but are less sensual than the Bantreay Srei period. They are designed with precision; the chin usually having a dimple which is typical of this style. Male figures have a finely shaped pointed beard. The eyes are wide and more often incised than sculpted. The head is occasio-

nally a little large for the body which is slender. Tiaras are rare and the jewellery, if any, discreet. The hair is drawn onto the top of the head to form a bulb shaped-chignon, held in place by a worked gold chain or a garland of flowers. We find these plaited hair styles on the sculptures of the Buddha. This is characteristic of the style and makes it easily identifiable.

The size of the figures remain modest. The hip line of the previous Art is used. The legs are generally stiffened by a buttress placed behind the heel, allowing for a refinement of the overall silhouette. The Sampot which is shorter exposes most of the abdomen by the elegant curves of its cut and rises high in the back where it is folded at the level of the waist into a large bow. The folds are of an extreme finesse. We are in the presence of an art of great quality. Less sumptuous than that of Banteay Srei, but more distinguished.

ANGKOR WAT STYLE

The Angkor Wat style takes its name from the royal temple of Suryavarman ll (1 1 13 — 1150), and starts from the reign of Jayavarman VI, his predecessor who died around 1107. It continues after the death of Suryavarman II, around 1150.

The alternance noted throughout the evolution of Khmer statuary between the two great tendencies, hieratism and frontality and elegence and softness, is found here.

The Art of Angkor Wat is in opposition to that of Baphuon, but at the same time is a prolongation of it. This art is a return to the frontality and hieratism. The forms once again become massive, the shoulders are larger, the torso, often naked, swells to a heavy and conventional shape evoking the aesthetic of the early tenth century; the proportions affirm a hieratism without moderation. But at the same time, if the statue is not submitted to strict iconographic norms, the statue loses its stiffness and becomes more human. This is the case of female figures where the face is often more expressive and we find a certain softness which reminds us of the beautiful faces of the Baphuon period.

The face of the Buddha is serene but denied of interior life; the eyes are rarely closed, the eyebrows are unbroken and almost straight, reminding us of the cutting design of the Koh Ker and Bakong faces. The beard and moustache tend to disappear. The lips remain thick and have lost their sensuality. The tiara and mukuta which are royal attributes adorn indiscriminately the images of Buddha, Vishnu or the king. We notice that the sculptor gives priority to an ideal of grandeur, slightly cold, to the detriment of the charm and softness of the face of the previous style.

The costume reminds us of the tenth century, as does the proliferation of ornaments and jewellery. Belts enriched with beautiful gold work decor and highly decorated necklaces often complete the tiara and cover-chignon. The female statues wear necklaces, bracelets and ankle chains. in general, the figures take on a new importance, characteristic of this style.

Another characteristic feature is the perfection of the work, the finish of the form and the precision of the incised decor which mark the works of this period.

But, the main innovation of the Angkor Wat style is the use of the representation of the meditating Buddha on the coils of the "Naga King" Muchilinda. The image comes from the previous style and will be largely diffused by the style of the Bayon which follows, to such a point that it becomes the symbol of Khmer statuary.

BAYON STYLE

Late twelfth, early thirteenth century.

Bayon Art shows a genuine mutation in Khmer Art statuary, linked to two important events: the sacking of the city of Angkor, the reconstruction which followed and the use of Buddhism as the official religion. This Art corresponds to the reign of Jayavarman VII (1181 - 1218).

The change in religion led to a change in iconography.

The proliferation of images of Bodhisattva covered the country with statues often of an imposing size.The statue of the standing Buddha, with his hands held out in an "assertive" gest, (the Abhaya-Murdra) becomes the fashion. The Buddha on Naga in the style of Angkor Wat becomes the preferred subject of the reign.

The climate of reconstruction of the country, under the difficult conditions and the increased demand, due to the development of the cult of the personality, led to an irregular and often mediocre finish. The use of poor quality stone or stone which had already been used and a preoccupation with stability led the sculptor to produce heavy legged and badly proportioned works. Apart from certain beautiful works, the form of the body is often a little scanty, but keeps a sense of anatomical observation reminiscent of the naturalism of some of the previous styles.

In general the effort and know-how of the sculptor is concentrated in the face, some of which are outright portraits.

They are usually marked with softness, even spiritualism. We are far from the preceding stiff and hard style of Angkor Wat. The face finds the great quality of the statues of Banteay Srei and Baphuon with the eyes often downcast and a discreet smile on the lips. The headdresses of the Devatas are generaly rich, enhanced with flowers and feathers. The hair is often plaited and lifted up onto the top of the head. On the male idols the hair is in the form of a high cylindrical chignon, left visible or decorated with ornaments. At its base, at the front, a small Buddha or the sign OM differentiate the figures of Lokesvara from Shiva.

The figure of certain high ranking divinities have no sculpted jewellery, but the ear lobes are pierced so as to receive earrings which were added, and they would have been completed with necklaces, bracelets and gold tiaras. This may have been finished with cloths or garments.

Finally, we note a voluntary rupture with traditional frontal and hieratic characteristics - through the work of certain statues in the round, such as the group of the Balaha horse at the Neak Pean temple or the deep reliefs of the terrasses of the royal palace. The large Garudas on the wall of the enclosure of Preah Khan at Angkor, or the giants

supporting the Nagas of the gates of Angkor Thom are evidence of this tendancy, which|reilnks it with the art of Koh Ker.

For reasons unknown, no doubt religious, but perhaps also political, and obviously in the aim of striking the imagination of the subjects, the religious themes are presented in magistral compositions visible to all. The gateways to the city of Angkor Thom are flanked by three-headed elephants and announce the sacred character of the site equivalent to the residence of Indra.

The monumental symbolism completely transform the statuary art, which tends towards the colossal, through the works that show it.

Two main themes are covered, the roadway lined with giants and the faced tower. Through these works, the statue is increased to the scale of the architecture and of the city. This is the most impressive creation of the Bayon Art and, perhaps, of Khmer Art.

Conclusion

The Bayon style and Angkorian Art continue after the death of Jayavarman Vll through certain works of which few exist today. From the thirteenth century, wood became the privileged material for sculptors and architects. The climate and insects have destroyed a large number of pieces and among those which have survived a lot are in an unusable state for the historian.

From the eighteenth century post-Angkorian statuary is marked by a Thai Art influence. This influence is added to a typical Khmer base.

The little space we have here does not permit us to present it in any greater detail, however succinct it may be.

Khmer sculpture through the chronology of styles

PHNOM DA STYLE

Corresponding to the Fou-Nan period of Cambodia's history. It divides into two periods: first half of the Sixt century and late sixth, early seventh century.

The Indian influence strongly affected the art and early Khmer statues of this period.

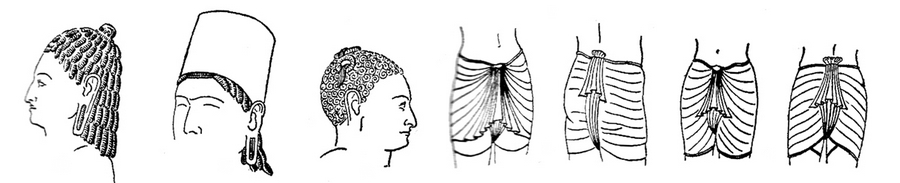

From observing the anatomy, morphology of the faces and the drapery of the garments the Gupta Art influence is evident. The figures are frontal and hieratic, often with large hips, the nose is long and hooked and the forms are full.

India had only known figures to be set in the wall, in bas relief or deep relief. For the Khmer artist the adventure would be to bring it out and dress it in space in a free standing form, In fact to make a sculpture in the round.

In the art of Phnom Da, the sculptor uses an arch in the form of a horseshoe which supports the most fragile parts.

At first this arch followed the full height of the statue, although sometimes was replaced by a beam placed horizontally at the height of the shoulders, these would be standard until the beginning of the ninth century.

Schist and sandstone were used indifferently; the beginning of the style seems to have a preference for schist.